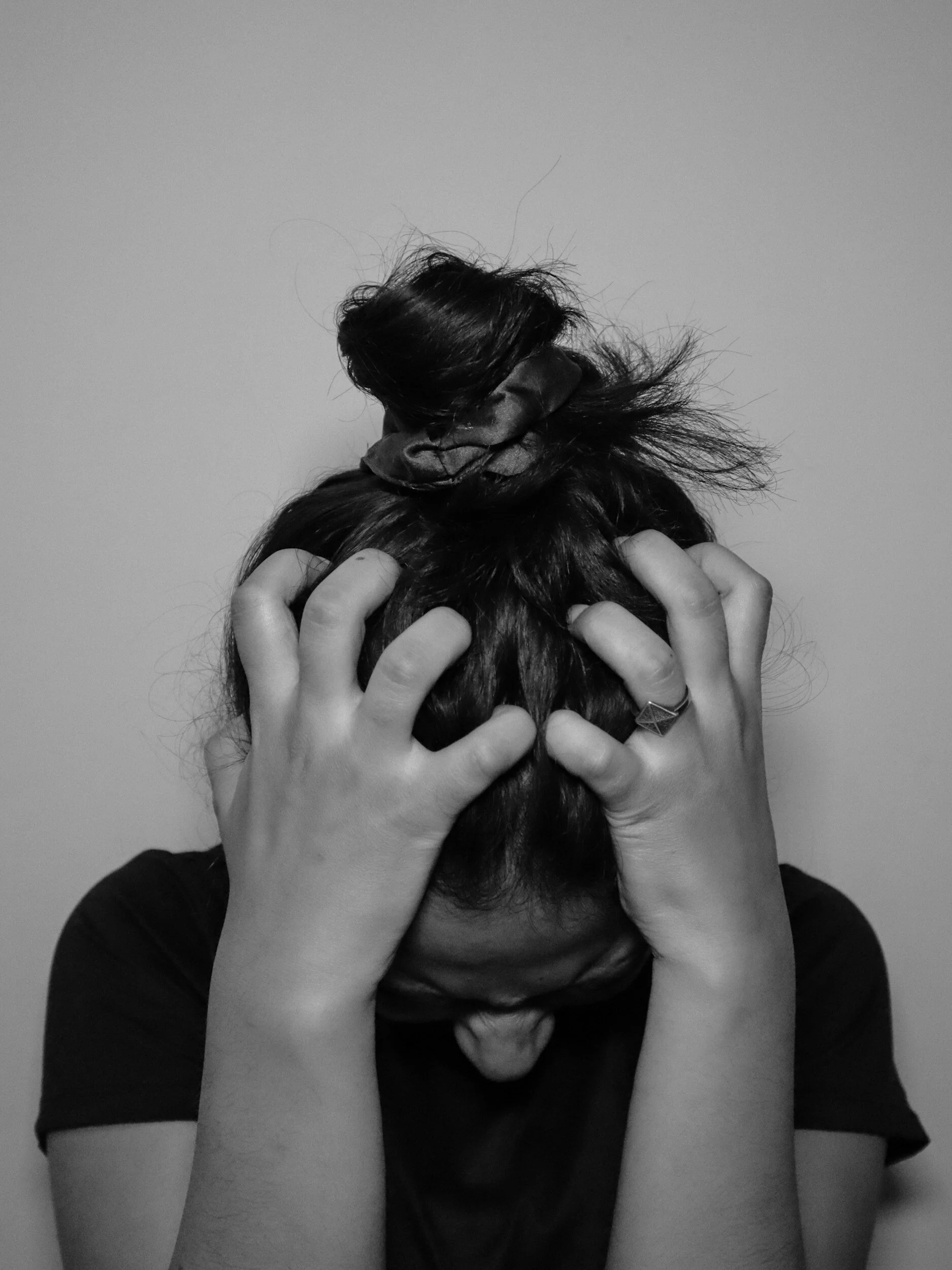

I find that not infrequently these days, I’m angry at God. Yes, I know that the current situation in Israel is man-made [and I use that term quite intentionally]. And I know that all of the death and destruction and physical and psychological trauma have been induced by human actions.

At the same time, I fully believe that World War II–and subsequently the Holocaust–ended because of the harsh Russian winter, which the Nazi army was unprepared for. Only God controls the weather and I think that God said to the Divine self, “Enough is enough; this is going to end now.”

And so, although I fully admit that it is the height of hubris to take offense that God has not yet chosen to step into this chaotic mess and resolve it, I find myself angry at the One who ultimately orchestrates what happens in this world.

And you know what? That’s okay. When we have a real relationship with someone [or with Someone], on occasion we will be angry with them. It doesn’t mean that we abandon the relationship; I continue to daven (pray) as I have each and every day of my adult life. It doesn’t mean that we retreat from being close to them or taking care of them; I continue to do mitzvot and live a life imbued by Jewish values to the best of my ability.

But I’m an adult who has spent much of my life grappling with theological issues. How might we address emotions such as anger at God with our students?

Many years ago, I had a 10th grade student who went through a major traumatic event when she learned that she would never be able to bear a child due to a congenital issue. She came to me and said, “I am so angry at God! How could God do this to me!” I assured her that it was fine to be angry with God for all of the reasons outlined above. And I validated that it was actually good that she had not lost her faith in God, but only temporarily her positive attitude toward God. But my validation wasn’t enough. As a teacher, I needed to help her understand that throughout history, our greatest leaders have been mad at God for a variety of reasons, and have gone on to live truly notable lives. First, I sent her to read Tehillim [Psalms] 22:

אֵ-לִ֣י אֵ֭-לִי לָמָ֣ה עֲזַבְתָּ֑נִי רָח֥וֹק מִֽ֝ישׁוּעָתִ֗י דִּבְרֵ֥י שַׁאֲגָתִֽי׃

אֱֽ-לֹהַ֗י אֶקְרָ֣א י֭וֹמָם וְלֹ֣א תַעֲנֶ֑ה וְ֝לַ֗יְלָה וְֽלֹא־דֻֽמִיָּ֥ה לִֽי׃

My God, my God,

why have You abandoned me;

why so far from delivering me

from my anguished roaring?

My God,

I cry out by day—You answer not;

by night, and there is no respite for me.

King David, himself, was furious with God. Granted, in this psalm, he admits that God is the Sovereign of the world and rescued our ancestors, but then goes on to say how he feels like a worm, despite the fact that he knows that God will ultimately save him.

I encouraged her to recite that psalm, even yelling it, rather than saying it, if she felt it would help. I also helped her work through ways she could elevate her life despite the major setback of never being able to bear her own children. We talked about biblical role models such as Devorah and Esther, who are never cited in the text as having been mothers. We looked at Bat Paro, the Pharaoh’s daughter, who raised Moshe as her own, even though his biblical mother was very much in the picture. And together we explored some modern Jewish change-making women, like Henrietta Szold, who never married nor had any children of her own, but made a huge difference in the Jewish world of the late 19th and early 20th century in both the United States and Mandatory Palestine. (Parenthetically, the student went on to marry and adopt two children.)

This personal intervention took a great deal of time, thought, and effort on the teacher’s part, and was worth every single moment I put into it. For after all, this is the crux of our pursuit: to work with each and every student on becoming the best person and the best Jew they can be while grappling with whatever cards God has dealt them.

Now, I need to implement some of these interventions on myself, so that I can move past the anger. Teacher, heal thyself!